A Queer Dharma: Metta, Privilege, and Oppression

Jan 10, 2022

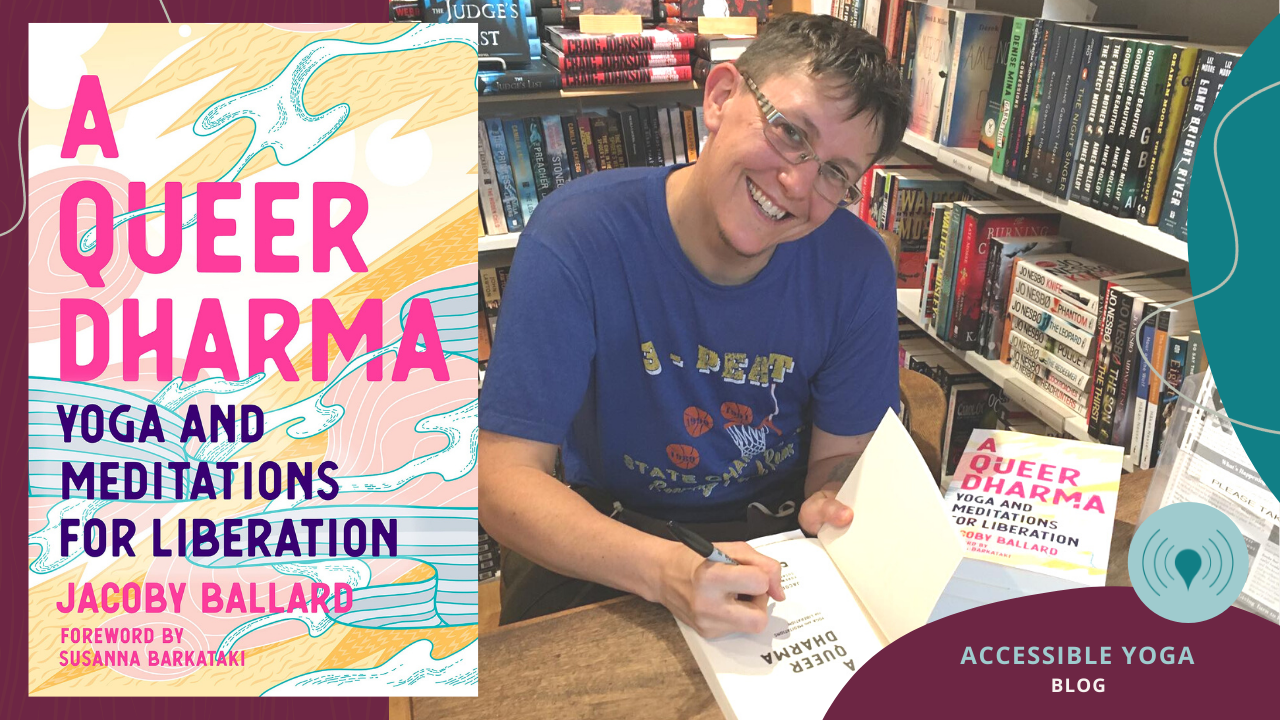

by Jacoby Ballard

This post is an excerpt from A Queer Dharma by Jacoby Ballard, published by North Atlantic Books, copyright © 2021 Jacoby Ballard. Reprinted by permission of North Atlantic Books. Buy Your Copy Now >>

The selected excerpt appears within the chapter entitled, "Loving Ourselves Whole." Dive deeper by joining Jacoby for his upcoming book club, beginning Friday, January 14, 2022. Sign Up Now >>

"Metta, Privilege, and Oppression"

There is a profound relationship between our personal practice and our collective experience, Larry Yang teaches. A connection exists between our internal and societal transformation. What we do in our practice is not just an internal experience. Our practice invites us to study the root of our behavior and whether it comes from love or fear. The soul has no gender, no race, no age, but is simultaneously richer for the particulars of our individual experience through race, age, gender, dis/ability, and other signifiers. We need spiritual communities to acknowledge each particular experience as part of the oneness or commonality of humanity. To go to oneness without recognizing the impact that oppression and privilege has on each of our experiences is called a spiritual bypass, a term coined by Buddhist teacher John Welwood.

Privilege has a lot to do with the spiritual bypass, because for some of us, or for some pieces of our experience, it is written into the fabric of our society as “the norm,” even within our sanghas and spiritual communities. It can be easy to disregard other experiences or move toward the idea of oneness because our experience has been affirmed all along. It is painful to look at the reality of hierarchy, separation, and suffering due to the rewarding of certain embodied experiences over others. Yet we must, if we are to recognize our full humanity or to see the full humanity of any other being. As a white person, because of structural racism I don’t have to look at racism as part of my daily reality, but if I don’t examine it I cut off a part of myself and certainly cut myself off from a majority of the world. Francis Weller, in discussing grief on a collective level, says, “We have not reconciled with the indigenous people of this country or the people we brought here from Africa. That grief is still there in our collective psyche. We’ve barely touched it.”1 To realize it and speak about it is to move toward and through the pain of it and access a deeper experience and understanding on the other side.

Many of us, due to marginalized identities, must look at oppression every single day because it is on our doorsteps, in our food, in the air we breathe, constructs our physical environment, and is inherited from our ancestors. At the same time, those in power deny, dismiss, resist, or avoid marginalized experiences and histories because it’s inconvenient to reckon with, painful to witness, or confusing to their worldview. This can create both a deep wound and an attachment to our experience because it’s painful in the first place, and then we have to fight for acknowledgment and recognition. This can be destabilizing and disorienting because we have this experience and then are told it’s not true, that it’s not so bad, and that it’s our own fault.

Eric Kolvig reflects, after years of work in the movement to end childhood sexual abuse, “The way that abuse is perpetuated through generations, is that the adults in the child’s life can’t know and are in denial, that it is too disruptive to do something.”2 Similarly, when white people can’t acknowledge the impact of slavery, Jim Crow policies, racist immigration policies, and the genocide of Native people, which all led to the wealth and power of the United States, then the violence of racism is perpetuated. We have to examine our particular experience and open ourselves up to the experiences of others that are vastly different from our own in order for healing to occur. In healing these oppressions, we give ourselves the opportunity to really see our true selves.

It is no wonder that those of us with marginalized identities respond to this trauma of perpetual dismissal, disregard, pain, blame, and shame with either an attachment and holding fast to our identities—reluctant to go toward oneness out of fear of erasure, assimilation, or death—or an avoidance of the pain and a desire to go directly to oneness, recycling the idea that we too don’t see race or other human differences. This is any human being’s instinctive reaction to pain manifested on a societal level. If we individually don’t have a practice of moving toward, investigating, and healing pain, then our society will not either.

In her poem “For the White Person Who Wants to Know How to Be My Friend,” Pat Parker wrote, “The first thing you do is to forget that i’m Black. / Second, you must never forget that i’m Black.”3 We need both to be recognized for our individual experience, and for our basic humanity to be seen and recognized, regardless of our embodiment or history. If we don’t recognize the particulars of our experience and the ways that they differ between each human being, as well as the patterns among various communities, that is a spiritual bypass. Larry Yang says, “We have to notice the particular on the way to the universal,” for otherwise the particular experiences of a small percentage of people (white, cisgender, male, nondisabled, young, and wealthy) on the planet are mapped onto all beings, and in that we lose so much richness and bypass so much suffering. This does not make the suffering and injustice go away, but rather more deeply ingrains it.

In marginalized communities we can run the risk of becoming attached to our identities and seeing how we are received in the world as who we really are. At the same time, any marginalized community has a well of incredible strength, courage, resilience, and spiritual depth because individual and collective survival depends on it. In this experience, we know, feel, and breathe our spiritual potential and our sense of oneness, but we cannot collectively arrive without a recognition of the particular realities of each of our experience, which is layered in identity. We do have so much more in common than what separates us.

Any marginalized position in society is an experience that is not recognized, portrayed, or centered. Our movements fight for this; we fight for our needs to be seen and recognized, for our experiences to be portrayed, and for our needs to be centered. At some point along the way, we need to loosen and let go of our identities as being the whole of who we are. The teachings tell us that attachment creates suffering, Larry Yang tells us that we are so much more than what meets the eye, and Jaya Devi teaches that the soul has no gender. So what if your beauty lies both within and beyond your Blackness? If my beauty lies within and beyond my queerness? There is a balance between loving ourselves within our identity and being attached to the identity.

Concurrently, within some social justice circles, in the effort to center those most marginalized and out of an unexamined reaction to systems of oppression, we may inadvertently or intentionally devalue or dismiss the pain of people with privilege. I have worked with white folks, men, and straight folks embedded in social justice to love themselves as well. This is important—our activism has to come out of a holistic metta, for those most targeted by systems of power and for those most protected. Jaya Devi’s guru, Ma Jaya, said that “pain is pain.” Regardless of whose it is, pain matters, and we must tend to it and heal it; if we don’t tend to it with attention and care, out of that pain grows rage, aggression, addiction, resentment, and fear. We see untended pain and trauma in current white supremacist movements; in a white anti-racist group I’m a part of, a friend said, “What if we really do have to care about white men’s pain?” We have seen what can happen if that pain is not tended to. Perhaps as a fellow white person I must tend to white men’s pain; that may be a corner of the racial justice movement for me. When I can tend to their pain, perhaps they don’t act out on my friends and siblings of color. Our identities influence how we are regarded and treated in this world, and we are so much more than what meets the eye.

If I exclude or push anyone away, my heart is not free. When we push someone out of our hearts there is a contraction, whether we feel superior or inferior in a hierarchy or condemn ourselves in the relationship. Our practice of metta is influenced by what we’ve inherited in our world—racism, classism, sexism, transphobia, ableism, homophobia—whether we’ve been harmed or protected by these systems. We begin with working deep within our hearts, and then having our words and actions match our greatest intention to welcome everyone into our hearts. When we aspire to have the eyes of a bodhisattva, to look upon all beings with love and compassion, as a community and individually, it inevitably shifts how we show up in community.

Sharon Salzberg tells a story of her experience in working with metta:

After I had spent these six weeks doing the metta meditation all day long, my teacher, U Pandita, called me into his room and said, “Say you were walking in the forest with your benefactor, your friend, your neutral person, and your enemy. Bandits come up and demand that you choose one person in your group to be sacrificed. Which one would you choose to die?”

I was shocked at U Pandita’s question. I sat there and looked deep into my heart, trying to find a basis from which I could choose. I saw that I could not feel any distinction between any of those people, including myself. Finally I looked at U Pandita and replied, “I couldn’t choose; everyone seems the same to me.”

U Pandita then asked, “You wouldn’t choose your enemy?” I thought a minuteand then answered, “No, I couldn’t.”

Finally U Pandita asked me, “Don’t you think you should be able to sacrifice yourself to save the others?” He asked the question as if more than anything else in the world he wanted me to say, “Yes, I’d sacrifice myself.” A lot of conditioning rose up in me—an urge to please him, to be “right” and to win approval. But there was no way I could honestly say “yes,” so I said, “No, I can’t see any difference between myself and any of the others.” He simply nodded in response, and I left.4

In relationships with colleagues, when I am deliberately working across race, class, and sexual orientation differences, inevitably the systems of oppression arise. It is par for the course. My practice of equanimity teaches me to take the larger view, the larger perspective, rather than getting caught in the drama of the moment, considering, “Who is this work serving? What might happen in the future if we build this relationship?” And my practice of metta encourages me to plant seeds of love, which will overcome the many seeds of hate that have been planted and cultivated for centuries. I have come to expect that dynamics of oppression and privilege will arise in any relationship, and to trust that my practice can hold them. They may break a relationship or make it stronger; it depends. Systems of oppression are dismantled through relationships, forgiveness, accountability, and leveraging privilege for the benefit of all. If I can hold that intention in my heart through the difficult conversations regarding my own words or actions that uphold white supremacy, transphobia, and ableism and that harm myself and my family daily, and slow down and listen when a wound of mine or a coworker’s is scratched, I can grow my heart wider and be in integrity.

Metta has been one of the most transformative practices in my life, and I’ve seen evidence because my relationships have improved over time. One of the original co-owners of Third Root once commented on how I have become kinder over the years. In my relationships, how and what is communicated, how authentic and real we each can be, and the ways that we show up to support or allow in support has shifted. I’ve also seen a shift in which relationships take more of a center stage (those that are more loving, honest, and mutual) and which have fallen away (those that are more superficial, based on gossip, or one-sided in efforts to maintain the relationship). My intimate partnership has improved and relationships with my family, relationships with colleagues, and the ways in which I interact with rude “strangers” (or even seeing them as “strangers” at all) have become more skillful, as have the ways I care for myself. I enjoy my life more and feel more connected.

The practice of metta involves faith: faith that this practice makes a difference for us and in the world. At the end of many classes and retreats, we send out metta to all beings, or dedicate the merit to either specific communities that are in the midst of difficulty or to ourselves. Sometimes this can feel trite or sentimental. Other times it can feel mechanical. The laws of karma dictate that the energy that we put out there is the energy that comes back to us, yet its timing is capricious and undetermined. We are entitled to our actions, but not the fruit of our actions. Our actions will inevitably have some effect—protecting us, resculpting our own brains, creating friendships and connection, and healing where harm has occurred—but the effect is out of our control.

1 Tim Mckee, "The Geography of Sorrows: Francis Weller on Navigating our Losses," The Sun, October 2015

2 Eric Kolvig, "What Matters," October 15, 2015, in Dharma Seed, podcast, MP3 audio, 45:53

3 Pat Parker, "For the White Person Who Wants to Know How to Be My Friend," Callaloo 23, no. I (2000): 73

4 Sharon Salzberg, Lovingkindness: The Revolutionary Art of Happiness (Boston, Shambhala Publications, 1995), 32

Jacoby Ballard (he/they) is a social justice educator and yoga teacher who leads workshops and trainings around the country on diversity, equity, and inclusion. As a yoga teacher with 20 years of experience, he leads workshops, retreats, teacher trainings, teaches at conferences, and runs the Resonance mentorship program for certified yoga teachers to find their niche and calling. Jacoby is the author of A Queer Dharma: Yoga and Meditations for Liberation (North Atlantic Books, 2021).

Jacoby Ballard (he/they) is a social justice educator and yoga teacher who leads workshops and trainings around the country on diversity, equity, and inclusion. As a yoga teacher with 20 years of experience, he leads workshops, retreats, teacher trainings, teaches at conferences, and runs the Resonance mentorship program for certified yoga teachers to find their niche and calling. Jacoby is the author of A Queer Dharma: Yoga and Meditations for Liberation (North Atlantic Books, 2021).

In 2008, Jacoby co-founded Third Root Community Health Center in Brooklyn, to work at the nexus of healing and social justice. Since 2006, Jacoby has taught Queer and Trans Yoga, a space for queer folks to unfurl and cultivate resilience and received Yoga Journal's Game Changer Award in 2014 and Good Karma Award in 2016. Jacoby has taught in schools, hospitals, non profit and business offices, a maximum security prison, a recovery center, a cancer center, LGBT centers, gyms, a veteran’s center, and yoga studios. He lives with his partner, child, and innumerable plant friends on unceded Goshute, Ute, Paiute, and Shoshone land, now known as Salt Lake City, Utah. More at jacobyballard.net.

Join Jacoby for A Queer Dharma Book Club

Fridays, January 14th - February 18th, 2022

Fridays, January 14th - February 18th, 2022

12pm – 2pm PT | 1pm –3pm MT | 3pm – 5pm ET

Choose from two tracks: an LGBTQIA2S Track and an Ally Track. Participants are encouraged to choose the track that most aligns with their experience and self-knowing.

Pricing is tiered to promote equitable financial access. Scholarships are available to those interested in the LGBTQIA2S Track.

A Queer Dharma Book Club is for readers who wish to deepen their understanding and practice with the author, in real time. Jacoby Ballard is an award-winning social justice educator and yoga teacher with 20 years of experience as a leader of workshops, retreats, teacher trainings, and mentorship programs. The group will come together every Friday for six weeks to discuss specific chapters, engage the supportive practices, and spend time in Q&A with Jacoby.

This 6-week space will teach you how to:

- Utilize supportive heart practices for social justice work

- Improve your relationships with friends, lovers, colleagues, and family members

- Use the book as a text in your personal practice & teaching

- Understand the unsavory dynamics of the “yoga industry” and how to ethically maneuver within or around it

Register Now >>

Still want more?

Jacoby was featured on the most recent episode of the Accessible Yoga Podcast. Listen below, or head to the episode page on our site to access the full transcript.

You can also practice Metta Meditation with Jacoby via this recorded offering from their YouTube channel.

Content warning: Jacoby's potent introduction to this meditation includes mentions of racialized bullying and youth suicide. If you prefer to start listening at the beginning of the meditation practice, you can jump ahead to minute 5:37.

Finally, Jacoby was a keynote speaker at the recent Accessible Yoga Conference Online in October 2021! Access to all conference replays, including Jacoby's talk, is still available for purchase.

Stay connected with news and updates!

Join our mailing list to receive the latest news and updates from our team.

Don't worry, your information will not be shared.

We hate SPAM. We will never sell your information, for any reason.